Posted 31 January 2001 - 13:04

And more generally about Hudsons, the story referred to above:

CLIVE GIBSON, at one time foreman of Frank Kleinig’s workshop, told me recently that just how much

Hudsons and Terraplanes played a part in racing in the thirties and forties. So I asked him to put

something about it on paper for the benefit of readers, the result follows.

FIRST OF ALL there is the issue of just how many people raced Hudsons and Terraplanes over the three

decades during which they competed. Here is a list, and there are many names there that might surprise you:

· Frank Kleinig (McIntyre Hudson and Kleinig Hudson 8)

· Les Burrows (1935 Sports Tourer & other variants)

· George Bonser (Terraplane)

· Bob Lea-Wright (Terraplane)

· Bill McIntyre (same two cars as Kleinig)

· Bill Bullen (Alvis Terraplane)

· John Crouch (Alvis Terraplane)

· John Snow (Alvis Terraplane & Hudson)

· Laurie Tyson (Terraplane)

· Jack Saywell (Railton 8)

· Bill Murray (Terraplane)

· Jack Murray (Terraplane - Kurrajong Hill, 1935)

· Kevin Salmon (McIntyre Hudson 8)

· John Barraclough (McIntyre Hudson 8)

· Joe Buckley (McIntyre Hudson 8)

· Jim Fagan (Hudson 8)

· Neil Baird (Terraplane)

· Ted Harris (Terraplane)

· Harry Beith (Terraplane)

· Stokes (Terraplane)

· Alby Johnson (Terraplane)

· Bob Burstall (Terraplane)

· Earl Davey-Milne (Bugatti-Hudson 8)

· Russell Kinsella (Terraplane)

· A McIntosh (Terraplane)

· Bill McLachlan (McIntyre Hudson)

· Ron Reid (Carpenter Terraplane)

· Peter Denman (Terraplane (?))

· Arthur Wylie (McIntyre Hudson)

· Belf Jones (Hudson 8 & Terraplane speedcar)

· Ray Pank (Lancia Terraplane)

· Norm Tipping (Terraplane)

· Bob Ledwidge (Terraplane)

· P G Brown (Terraplane)

· Campbell McLaren (Terraplane - Rob Roy 1948)

· Cappy Wood (Terraplane speedcar)

· Alf Bowers (Terraplane speedcar)

· Bill Ford (Terraplane)

We found a couple more, I can't remember who now...

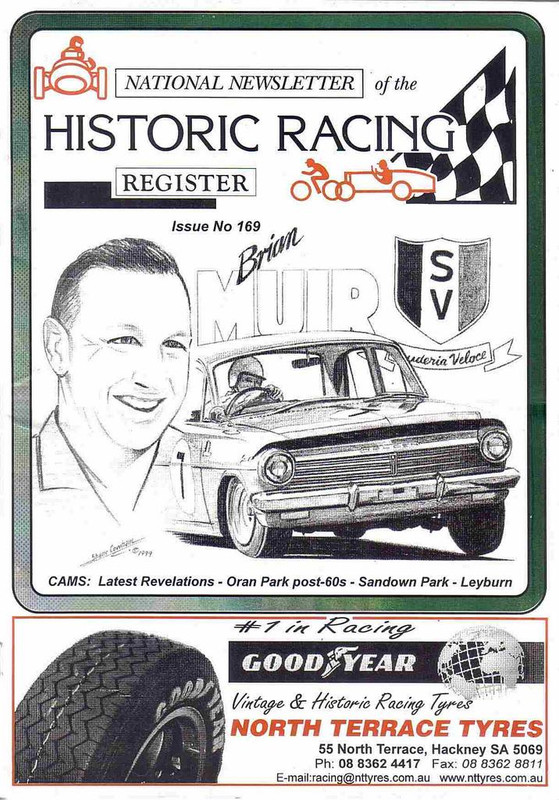

And, in the Historic Racing era (post 1960)

· Peter Hitchin (Terraplane)

· George Gilltrap (Carpenter Terraplane)

· Ray Bell (Terraplane - Collingrove 1977)

We can also add to that the two owner/drivers of the Burrows car in its Ford-powered form:

· Peter Wallace (Barracuda Ford)

· Mike Morris (Barracuda Ford)

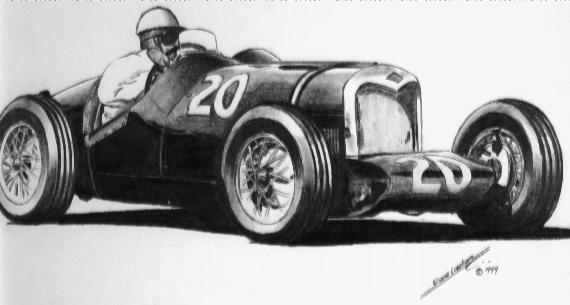

It’s interesting to see the make represented in the AGP, in which they were not eligible to compete until

1936 at Victor Harbor. From then they were seen in each race until 1950, missing 1951 (very interesting

thing, their lack of usage in WA), then rejoining the entry list from 1952 to 1955 (though none started the

race in 1954 or 1955).

The Terraplane engine began life in the Essex in the early twenties, but revisions in 1930 and a new

offering of an eight in the thirties in the Hudson range brought forth the foundation engines for their entry

into competition. Essex was among the makes to play their part in intercity record-breaking and Maroubra,

but usually the F-head four. The Essex name was phased out in 1932-33 through Essex Terraplane to

Terraplane, from 1937 the name became Hudson Terraplane.

Why were they chosen for such strong representation in competition, especially with big-end lubrication

dependent on the splash feed principle?

“They were very light,” says Clive, “a hundred pounds lighter than the other American engines of the

same size. They revved hard, and they were short blocks, so you could fit the six in where a four fitted.”

The factory had addressed the splash feed problems as time went by. By 1929 there was more oil being

pumped into the trough through which the dippers ran to scoop up their oil. The pump filled the front trough,

then overflowed progressively towards the back troughs. This had its problems, too.

“Say someone was going down Bulli Pass,” Clive relates, “in second gear, then the oil wouldn’t flow

uphill into the rear trough, and so the rear big end would fail.” So in 1930 came the ‘duo-flow' in which oil

went to the front and rear troughs, then flowed over into the centre ones.

Light weight in the rest of the car was another factor in those cars built up entirely from Terraplane bits.

And the flywheel was very light, being made in Molydenum Steel and having an oil-bath cork clutch

attached. “The gearbox was half the weight of other cars’,” Clive says, while a look at axles and so on

quickly underscores the weight situation.

By 1934 the bolt-on crankshaft counterweights were done away with for the Terraplane, something that

Hudson had earlier adopted in other engines, and something that was almost unique in the industry. Hudsons

always marched to the tune of a different drummer, according to Clive.

To follow the history of just two of the drivers listed, the two most prolific ones, we’ll look at the Les

Burrows and Frank Kleinig experiences with Hudsons and Terraplanes.

Burrows, a dealer in Bowral, had been showing off Essexs for some time before getting a 1935

Terraplane Sports Tourer. In this car he won a Phillip Island race in 1935, but then drove the McIntyre

Hudson at Robertson Hillclimb later in the year.

Impressed by the eight’s power, he ordered a new 1936 model minus body and installed the 1935

Terraplane body on the new car. It was in this car that he and his riding mechanic took their wives on the SA

Centenary Trial from the Sydney start to Adelaide, then the guards were removed for the Grand Prix. The

1935 engine was destined for use later on in a 1933 Terraplane which was shortened and run briefly with the

original engine. With a Propert body and the ’35 engine and wire wheels, then a ’38 grille, it was the

definitive Burrows car that was raced so much - and finished the Lobethal race on three wheels.

It’s here that the history intertwines. Kleinig was put into the McIntyre car for a Hillclimb at Hartley, near

Lithgow. Previously he had ridden as mechanic with Joe Buckley, but Buckley broke his neck in a rollover

at Phillip Island and Frank became the regular driver.

He literally drove the wheels off it, the car finishing up sitting on its belly after breaking the spokes out

as he cornered it hard. McIntyre was unperturbed, he bought a set of 1936 disc wheels and upgraded the

brakes at the same time.

Gus McIntyre was the owner of several cinemas, a business that became a growth industry during the

twenties and boomed in the depression. “They say he spent 10,000 pounds on that car,” says Clive, “and in those days a Rolls Royce cost about 3000 pounds.”

It was built for the race proposed for 1936, with its start in Algiers and the finish in Johannesburg - and a

lot of country in between, 8600 miles of it. Gus had the car built with a secret weapon, literally an extra bow

in its quiver, as it was made to take a spare engine in the boot! Then the race was cancelled. . .

Alongside this car Kleinig developed the MG-chassised racer, a car he kept on developing until 1954.

This was undoubtedly the most famous Hudson Special, the fastest, one of just three Australian Specials that

took the race up to the imported cars that should have been dominant.

Kleinig challenged Barrett’s Monza before the war at Lobethal and Bathurst, wrested the Rob Roy record

from Tony Gaze and the Alta in 1948, and according to Clive would have won the 1953 AGP.

“It was the hottest we ever had it at Albert Park,” he recalls. “we had changed the radius on the cam

followers* on cylinders 2 & 7 to reduce the overlap (we had a problem with 1 & 8 taking the fuel and

starving the other two cylinders#), and it had 12 or 13:1 compression ratio with crowned pistons.”

Remembering that this 4.2-litre straight 8 was a side valve engine, it was still a very tall order. “Curley

Bryden was second in that race, so many cars dropped out,” Clive continues. The Maybach had a long pit

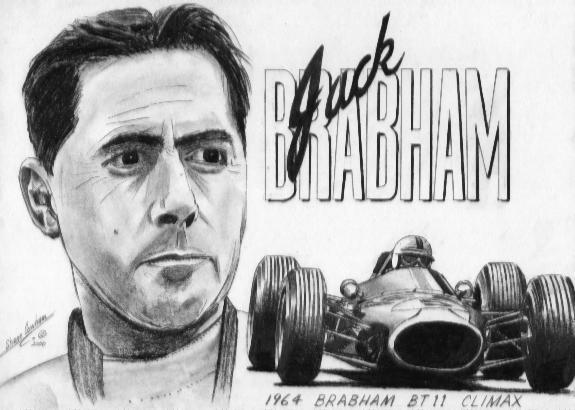

stop for fuel and was overheating, Brahbam’s Cooper ran bearings in practice, Davison’s HWM Jaguar fell

out very early. “At the end of the first lap Jones, Whiteford and Frank could have been covered by a blanket,

then the seat belt broke . . .”

With the cart-spring suspension of the pre-war car bouncing him around mercilessly, Kleinig was

clinging to the gearlever for stability as he changed gears and smashed third gear, then second gear in the

modified Mathis 4-speed box. The belt buckle was hanging down beside the car, catching on the road,

flicking off the wheel and slicing into the back of his elbow. “You could see the bone,” says Clive.

Still the car finished, the only time it finished an AGP. “And that one was a full 200-miler!” Bud Luke

was lap-scoring and reckoned they were third, but Frank knew that meant nothing and accepted the seventh

place he was given.

By the Southport race in 1954 Kleinig had seen that big changes would be necessary. A Maserati body

was fitted and the car was changed to a monoposto, still on the original MG chassis, but now equipped with

a Peugeot 203 independent front end. Clive recalls that the steering column had several universal joints,

“part of the shaft went through the gap in the inlet manifold. . .”

A Hudson rear axle had one axle shortened to offset the diff and allow him to sit lower than he could over

the driveline, the Mathis gearbox (with its multitude of different ratios) rebuilt, and a radiator core seven

inches thick made up to cope with the lower bodywork and still, hopefully, cool the engine. “We reckoned

the water pump had to be lowered, too, but didn’t have time to get that done,” Clive told us.

En route to Queensland the car was unloaded near Armidale and taken for a five mile test run up the

highway. It boiled. More work was needed, but it was four hundredweight lighter. The problem is that it

never did, for the special lightweight battery made by Lion for the still ill-handling car caved in on race day

and Kleinig was out. He resisted all attempts to get the car out from that meeting on, never driving it again.

Was there any point, with cars like Cobden’s Ferrari now on the scene, the second Lago Talbot, etc?

The only contemporary racing subsequent to this of Hudsons or Terraplanes was accomplished by that

old 1933 Burrows chassis. Its Propert body put aside in the late forties by Bill Ford, it was entered in the

AGP of 1955 as a part of Bill’s racing, and continued running until the closure of Mt Druitt and the Easter

meeting at Bathurst in 1958, not entering the AGP that year.

As mentioned in the listing of drivers, the car became the Barracuda Ford in the sixties, with the Propert

body, the grille Ford had fitted before the 1948 AGP and a Ford OHV V8. It reverted to its canvas-bodied

single seater form when Peter Hitchin resurrected it for Historic racing.

Internationally the Hudson engine was recognised, too. A team of three cars raced in the French GP of

1936, Railton and Brough Superior both used the Hudson engine, while at home they took out all the stock

car Hillclimb records under the auspices of the American Automobile Association by the end of 1933. In

addition, a Hudson averaged 86mph round the circle on the Bonneville salt flat for 24 hours in 1937. In

Australia the cabbies liked them, the lasted well and were economical.

Some of the variants raced were interesting. Bullen’s Alvis was the car Phil Garlick had put over the top

at Maroubra, and when the supercharged replacement Alvis engine blew Kleinig fitted the Terraplane 6 - to

repay John Snow the ten quid he had needed to get home from Lobethal in 1939. The Charlie East/Cec

Warren Bugatti Type 37 was equipped with a Hudson by Earl Davey-Milne, while Geroge Bonser planned

a similar transplant for another Bugatti, but it finished up with an ugly body and a Dodge 6 in the hands of

Doug McDonald in Brisbane. Seeing this horrifying concoction, Bonser requested its return to his care, but

could never retrieve the car.

When John Crouch took the Burrows car to Heathcote Road (between Liverpool and Engadine) for a

sprint meeting, he did a standing quarter in 16 seconds. When Kleinig wanted to beat that Gaze/Alta record

he ran it out to over 7000rpm to save a gearchange. “After that they changed the camber on the last corner,

and then they shortened the climb so there was more room to pull up,” Clive adds, lamenting that Frank’s

record should have lasted longer.

Such a willing engine, particularly in 6-cylinder form, so available, so light, it was no wonder that these

cars proliferated against the onslaught of the Ford V8. But the most successful of them was the expensive

McIntyre, and some time soon we’ll have a story about the Wakefield Trophy, a year-long event this car won

twice.

RAY BELL

* Kleinig never ran a modified camshaft, but altered valve timing by using different radius grinds on the

followers. Standard was a 3” radius, but he used up to a 6” radius depending on how much additional

overlap was required.

# From time to time different methods of overcoming this were tried. Different spark plugs was the most

usual, but the final solution was going to be the separating of the ports. Once the early model blocks were

all used up - just after the war, a 1937 block with bigger ports was used, and these were big enough to put

a sheetmetal divider up the centre. Others did it, but Kleinig never got to try it. To see the problem, check

out the firing order - 1.6.2.5.8.3.7.4 - which gave only 90 degrees of crank turn between adjoining cylinders.

With extra overlap the charge would be still going into the first to open. Why it didn’t concern other

cylinders is a mystery... Are there any whizzes out there that could solve this today?

This latter question was solved by Jim Bertram, but I can't post the diagram he drew...

[p][Edited by Ray Bell on 01-31-2001]