https://www.macsmoto...xle/#more-81728

Advertisement

Posted 10 January 2021 - 06:42

As I wrote on Macs site, an over rated, over weight thing that fries its oil. Pinion is so low it fries the oil and uses a lot more power to run.

The only thing going for it is the number of ratios available that suits motorsport,, most OEM ones suited to light trucks!!

There is no end of better more efficient diffs around. Ford used the Dana, and the 8.8" Salisbury used currently.

I never had any issues with the GM 10 bolt [Australian] except for a lack of ratios. I used GM axles which were far stronger than the Ford ones, both fairly universal 1 1/8" 28 spline. The Ford ones lasted 15 laps! The GM ones are still in the car near 30 years on.

And yes I used one for ratios only in my Sports Sedan. I used to change the [vegetable limslip] very meeting as it stank and would go off. Normal gear oils drained with a metallic tinge. I suspect synthetic would be an improvement but not generally available 20 years ago

For a road car they live ok, though are still too heavy and drag too much power.

And have not been used in a roadcar for over 40 years!

Posted 12 January 2021 - 00:16

To each his own but the entire U.S. high performance industry seems to think you are wrong. ![]()

Even though it was developed more than 60 years ago, the Ford 9-Inch is the rear axle of choice throughout the American high-performance world. Here’s why.

When the Ford Motor Co. unveiled its 1957 vehicle line in October of 1956, in the press materials there was only brief mention of a new rear axle assembly for its cars and light trucks. Engineered in-house and produced by the company’s Sterling Axle Plant on Mound Road, which had opened only a few months earlier, the axle proved to be a winner—beyond anyone’s wildest dreams, actually.

At the time, no one could have foreseen that today, more than 60 years later, the Ford 9-Inch is ubiquitous all across the American racing and performance scene. ![]()

Design features that made the 9-Inch so popular:

+ The carrier housing is a front-loading dropout type, also known as a “banjo” or “pig” style, which is far more mechanic-friendly than the more common Salisbury/Spicer design in which the differential carrier loads into an integral axle housing from the rear. Here, backlash and pinion-depth adjustments are quick and easy, and gear ratio changes can be accomplished in minutes.

+ The pinion-shaft assembly is carried in a separate, detachable sub-housing (a cartridge, as some describe it), which simplifies adjustments even further and allows beefy, large-diameter bearings and yoke.

+ The axle shafts are secured in the housing with sturdy retainer plates at the housing ends, rather than with C-clips inside the carrier, a setup that is not terribly safe or suitable for serious racing use.

+ The ring gear (crown wheel in the Queen’s English) is a generous 9.0 inches in diameter, which allows the axle to withstand extreme torque loads and lent the rear axle its familiar name. Ford also manufactured axles of this design with 8.0-inch and 9.38-inch ring gears for various applications, and at one time or another, the axle family has been used in virtually every U.S. car and light truck platform produced by the company between 1957 and 1986.

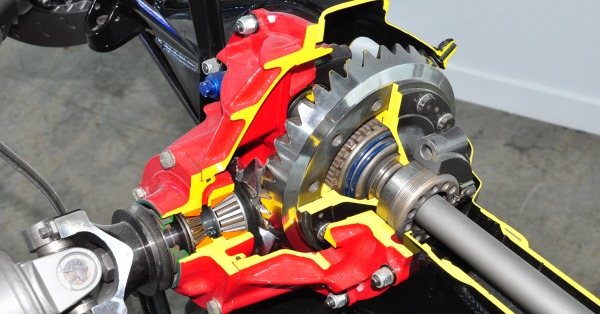

So by fortune or design, the 9-Inch checks a number of important boxes for high-performance use. And when we dig a little deeper, we can see even more significant advantages, starting with a property called hypoid offset, above. In the hypoid gearset, introduced by Packard and Gleason Gear Works in 1926, the pinion gear is offset from the ring gear’s centerline, rather than centered as on a conventional spiral-bevel gearset. The result is a sort of bevel/worm gear hybrid, combining both meshing and sliding action between the gear teeth, and the increased contact area produces a stronger, quieter gearset. (Hypoid axles also allow a lower driveshaft and flatter passenger floor, surely the main reason they were embraced by the American car industry.)

In most U.S. passenger car drive axles, hypoid offset is generally in the 1.25-in. range (top left gearset). But on the Ford 9-inch (lower left gearset) the offset is much greater: 2.38 inches. This provides an even longer, deeper tooth contact (yellow arrow). The increased contact area does come at some cost: greater friction, more heat (often requiring a differential cooler), and a small but significant increase in mechanical loss— around two percent. In most applications, racers find the sacrifice is more than worth it. But it’s surely no coincidence that the 9-Inch was discontinued on production cars when fuel efficiency became a prime concern.

One more advantage of the 9-inch worth mentioning, as indicated by the red arrow above: Unlike most every other unit of its class, the Ford carrier includes an extra journal on the nose of the pinion to support a bearing set deep in the case, which stabilizes the gearset against deflection and allows a shorter, more compact pinion shaft.

With all these valuable attributes, the Ford 9-inch is far and away the favorite of the American high-performance scene, from street rodding to NASCAR, and it has been for decades—despite the fact that Ford hasn’t offered the unit in a production vehicle since 1986. Every component, down to the last spacer and seal, is now available in the performance aftermarket. Like a small-block Chevy V8 or a Fender guitar, an entire 9-inch axle can be assembled without a single original factory part. Specialist suppliers including Strange, Mark Williams, and Moser Engineering offer a complete range of components and assemblies for every conceivable purpose.

+ The carrier housing is a front-loading dropout type, also known as a “banjo” or “pig” style, which is far more mechanic-friendly than the more common Salisbury/Spicer design in which the differential carrier loads into an integral axle housing from the rear. Here, backlash and pinion-depth adjustments are quick and easy, and gear ratio changes can be accomplished in minutes.

+ The pinion-shaft assembly is carried in a separate, detachable sub-housing (a cartridge, as some describe it), which simplifies adjustments even further and allows beefy, large-diameter bearings and yoke.

+ The axle shafts are secured in the housing with sturdy retainer plates at the housing ends, rather than with C-clips inside the carrier, a setup that is not terribly safe or suitable for serious racing use.

+ The ring gear (crown wheel in the Queen’s English) is a generous 9.0 inches in diameter, which allows the axle to withstand extreme torque loads and lent the rear axle its familiar name. Ford also manufactured axles of this design with 8.0-inch and 9.38-inch ring gears for various applications, and at one time or another, the axle family has been used in virtually every U.S. car and light truck platform produced by the company between 1957 and 1986.

Edited by Bob Riebe, 12 January 2021 - 00:22.

Posted 17 January 2021 - 23:42

Indeed. Because the 9-inch runs so much more hypoid offset, it provides more tooth contact (good) but generates more frictional loss and heat (bad). Jeff Smith ran a fairly vigorous chassis dyno test A-B and determined that the penalty was around 2 percent.

The way I hear it, NASCAR is adopting the same IRS transaxle now used in Australia Supercars for 2022.

Posted 18 January 2021 - 15:58

As long as everyone is running the same spec axle, the efficiency—even performance— is pretty much of no import. Just make it super reliable.