Posted 22 January 2002 - 21:37

This is what Jurgen Schwartz wrote in an old Christopherus (the German Porsche Mag) about Porsche first Indy-try. A lot of hard work....

Porsche had been toying with the idea of having a go at the Indy since the mid-1970s. The Stuttgart sports car company had been winning trophies everywhere: in Formula 1 events, in the Le Mans 24 Hour Race and the Monte Carlo Rally. But the Indy was the big one, with its trophy which is so massive and heavy that a grown man can barely carry it, especially after driving 500 miles in a circle at an average speed of 320 km/h.

In 1977 the company's interest in the Indy began to take on a tangible form: the first plans were drawn up for a new engine based on the turbocharged flat-six unit. Initially, project leader Helmut Flegl and engine designer Valentin Schaeffer maintained a discreet silence about their intentions. Flegl had already earned himself something of a reputation in racing circles: it was he who had masterminded Porsche's assault on the CanAm sports car championship from 1971 to 1973. The company had won the title twice, but its participation in the series had ended with a major controversy: its obvious technical superiority over its American rivals had led the organizers to change the rules, outlawing the turbocharger which had powered the Porsche cars to victory. Thereupon Porsche withdrew from the series, whose attraction for the public and the media subsequently waned.

Hence Porsche already enjoyed a certain notoriety in the USA. When the company announced in December 1979 that it was going to take part in the Indianapolis 500 Miles Race the following year, its American competitors grew somewhat resentful, remembering the humiliations of the past in the CanAm series. Nobody said it in so many words, but the general fear was that the Germans were going to come over and mount a Blitzkrieg Operation to win the American race. The pre-war victories of Mercedes and Auto-Union may also have contributed to this anti-German mood.

However, Porsche's first Indy project was a relatively low-key affair. The thrifty Swabians had invested a mere two million dollars in the development phase - sum roughly equal to the prize money which Porsche cöuld expect to receive if it won the annual race. Two million dollars was not enough to build a complete car. Anticipating the successful Formula 1 partnership between TAG and McLaren a few years later, Porsche decided to team up with an experienced firm from the US scene. When the car was revealed to the public gaze for the first time at press conferences in Stuttgart and New York, the Porsche name was seen to be modestly stenciled below the windshield at the front of the cockpit. On the flanks of the car, in large letters, was the name Interscope.

The Interscope company was owned by a bearded and bespectacled 27-year-old whose appearance successfully disguised the fact that he was the wealthy heir to a chain of successful department stores. The Interscope racing team was Ted Field's spare-time hobby, which he pursued with exceptional zeal and devotion: his cars had taken part in a number of serious races, mainly in the IMSA series. In Jim Chapman he had hired one of the most experienced team chiefs in the Indy circus. And the chassis on which the Porsche engine was to be mounted had been desijzned bv Roman Slobodynskj, also a name to be reckoned with in the racing world.

Interscope and Porsche had already worked together on the American IMSA sports car series. In January 1979, for example, an Interscope Porsche had won the Daytona 24 Hours Race in Florida, the American equivalent of the Le Mans 24 Hours Race. In addition to Jim Chapman himself, the Le Mans winner Hurley Haywood and the 37-year-old Hawaiian Danny Ongais had taken it in turns to pilot the black Porsche 935, which at the express wish of the team owner Ted Field had been given the unusual number 0. lt was Ongais to whom most of the credit was due for the winning Porsche's lead of no less than 307 Kilometers over its nearest rival in the memorable Daytona Race.

At that time, 'Danny-on-the-gas' seemed a singularly appropriate nickname for the Hawaiian driver. He seldom spoke, letting his en-gine and accelerator do the talking for him. His opponents considered him the boldest and bravest member of the racing brotherhood. For twelve years he had been competing in the USAC championship, for which the 500 miles of the Indy are merely one of 15 events. But his success on that May weekend counted for more than his performance over the entire year. Ongais was under contract to Interscope, and in Porsche's view he was the right man for the j ob of making the initial assault on the Indy.

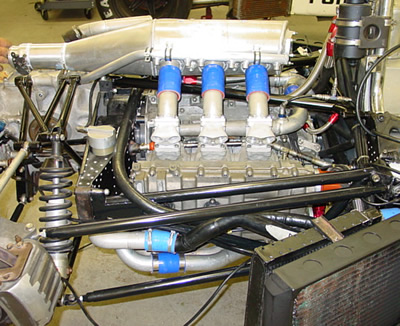

The first Porsche engine which was delivered to Interscope's Santa Ana headquarters in California was mounted on an old Parnelli chassis. The new car in which the engine was to be housed would not be ready until the start of the season in 1980. Since the Parnelli shell had previously been powered by an eight-cylinder Cosworth engine, the Interscope engineers had to build a sub-frame for the engine: unlike the "Cossie", the six-cylinder Porsche engine, which was similar to the unit used in the company's production cars, could not be fitted in the monocoque.

The Porsche engine was a tried and tested piece of automotive engineering which continues to perform sterling service on the roads in the 911 and 959 sports cars. The 935 and 936 had been successfully powered to victory in World Sports Car Championship events by the improved version of the 930 turbo, an engine which is still used today in the Porsche 962. Manfred Jantke, who at that time was Porsche's racing manager, described the 1979 Indy unit as "practically the last word in the development of our classic six-cylinder engine". With a displacement of 2,649.65 cc, the turbocharged engine was to deliver over 600 bhp. In accordance with the Indy rules, it had to use methanol instead of European high-octane gasoline.

Even at that time there was already a fuel limit for the Indy: the Maximum allowance was 1050 liters for the 500 miles. Long before the Formula 1 superstars began having to weave from one side of the track to the other in order to shake the last drop of fuel into the combustion chambers, the Indianapolis crowd had grown accustomed to the sight of cars grinding to a halt for lack of fuel.

With its aluminum block, the Porsche engine would have been one of the lightest on the circuit in Indianapolis. And it featured one particular detail which seemed to offer a considerable advantage over the cars of the Stuttgart company's more established rilvals: Cosworth and Foyt, with their eight-cylind.er engines and Offenhauser, with its four-cylinder unit. Porsche had come up with a new combined cooling system, using air, but dispensing with a fan, for the cylinders, and water for the cylinder heads. This system, albeit with a fan, had already been tested in World Sports Car Championship events and had been proved to be viable.

Hence, with its four-valve engine, the car seemed to offer solid grounds for optimism on the part of its constructors, as they pre@ared to embark on their adventure in the New World. "Indianapolis is a new and exciting challenge for us," racing manager Manfred Jantke declared, but added, on a more cautious note, "We are not coming to Indianapolis with expectations of instant victory." Instead, he emphasized the long-term nature of the Indy undertaking: "The project is intended to run for more than a single year. We are sure to need a good deal of time to catch up with our rivals - but with luck, perhaps we can even manage to beat them."

The stage seemed set for a successful attempt to compete at Indianapolis - only the timing of the venture was wrong. At the time of Porsche's secret preparations for the Indianapolis event, the American racing scene was skidding into a profound crisis. Since 1972, the USAC Championship series had been run on a stable set of rules. This era came to an end in 1977, when the participating teams founded a society to defend their interests against the all-powerful United States Automobile Club from which the USAC series took its name. The new group, which called itself CART, was modeled on the Formula 1 FOCA association, headed by the famous Bernie Ecclestone. His CART counterpart was the Businessman and racing equipe owner Roger Penske, with whom Porsche had successfully cooperated in the past. At the beginning of the 1970s, he had organized ]Porsche's participation in the CanAm series; in subsequent years he had become one of the most prominent team managers in the USAC Championship.

In 1979 CART - the acronym stands for Championship Auto Racing Teams - staged a rebellion. Under Penske's leadership the best teams organized a championship series of their own, in direct competition with the traditional USAC Championship. Only one member of the elite corps of US racing drivers remained loyal to the USAC - Anthony Joseph Foyt, who at that point had already won the In dy four times.

That same year, the Indianapolis event was the subject of a court case, when the USAC made an unsuccessful attempt to bar the rene-gade CART teams from the race, which was eventually won by - of all people - Penske's top driver Rick Mears. At the end of the year, Mears also became the first winner of the CART title. At the same time it became clear to all concerned that there was no room for two similar racing series in the USA. The spectators were staying at home, TV companies were canceling contracts, prize monies were dwindling, and the tire company Goodyear declared that it was only prepared to sponsor one championship. In view of all these factors, talks were initiated in the winter of 1979/80 with the aim of reuniting the two hostile factions. Thus the preparations for the premiere of the Interscope Porsche took place in a climate of extreme uncertainty. The rules governing what was allowed and what was banned in the construction of Indy cars had ceased to apply, and for several months the USAC and CART were unable to agree on a new set of regulations. In this muddled Situation, Porsche decided to stick by the traditional USAC rules. Jo Hoppen, who at that time was the company's US racing coordinator, explained: "We don't want to get involved in political controversy. We are here to compete at Indianapolis.

The car is built according to the Indianapolis rules, which means the rules of the USAC." In retrospect, Porsche's racing manager Manfred Jantke described how the company had been extremely worried about the Konfusion surrounding the rules: "However, we hoped that the two groups would reunite. And we had to decide one way or the other."

The uncertainty of that winter led to bizarre consequences. While the car was being tested on t he racing circuit in Ontario, the members of the Interscope Porsche crew noticed that helicopters kept appearing in the sky, hovering over the scene for several minutes at a time. This mystery was never conclusively solved, but everybody iavolved was certain that Porsche's anxious rivals were spying on the company in an effort to find out what sort of lap times Danny Ongais was clocking up with the new car.

Porsche had to put up with no end of prying and interference. In February 1980 the company received a highly unusual request from the USAC to allow an inspection committee to observe the testing of the Indy engine at Weissach. When the committee arrived, it was found to include one Howard Giert - an engineer with the rival engine manufacturer Foyt. However, the engine which these gentlemen saw at Weissach was unlikely to strike fear into the hearts of Porsche's American rivals: with a boost pressure of 0.8 bars, in accordance with the USAC rules, it delivered 574 bhp - a less than spectacular figure. In the preceding years, the USAC had instituted a handicapping system, stipulating different maximum boost pressures for the various engine sizes. The limit for eight-cylinder engines was 0.6 bars, for cars with six cylinders it was 0.8 bars, and for four-cylinder engines just over 1 bar. This rule was one of the controversial issues in the "peace talks" between the USAC and CART.

When the two rival bodies finally reached an agreement in March 1980, Porsche suddenly found its path to the Indy blocked by an insuperable obstacle. The old USAC rules had been changed: the boost pressure limit for cars with six-cylinder engines had been set at 0.6 bars, the same as for eight-cylinder engines. This new limit meant that Porsche would be giving away 80 bhp to its nearest rivals - a handicap which, nine weeks before the race, was impossible to overcome. To change the compression of the engine and develop a new fuel injection system and turbocharger would have taken four to six months.

This was the biggest setback caused by external factors which Porsche had faced in thirty years of competition. "The height of unfairness," Manfred Jantke protested: "The biggest disappointment I have ever experienced in motor sport." For several weeks Jantke attempted to negotiate with USAC and CART representatives, but his efforts were in vain. Thereupon the Porsche executive board took what was described in the official communique as "a grave and disappointing decision for the company." Porsche withdrew from the Indy before a single training lap had been driven. The ten engines and four cars which had been built to date were useless, fit only for a museum.

Even legal redress was out of the question. There would have been little point in suing the USAC for damages, since the club was longer responsible for the race, and Porsche's lawyers found themselves unable to put a case together. Driving an Interscope Cosworth, Danny Ongais eventually came seventh in what was one of the slowest races in the history of the Indy. Johnny Rutherford was the winner, with the low average speed of 230 km/h, because the race was repeatedly interrupted by accidents: for lap after lap the, drivers had to crawl round the circuit without being allowed to improve their position.

Eight years had elapsed since Porsche's first attempt at the Indy, when the company decided in 1987 that the time was ripe for a further assault. In the meantime, a number of things had changed. The CART had established itself as the organizer of the Indy and, following the unfortunate events of 1980, had done a highly professional job of managing the race and restoring its former luster. The rules had been stabilized, and Porsche had every reason to hope that, this time, it would not be subject to acts of official chicanery but would instead be welcomed into the fold of Indy competitors. The company had also enlisted the services of Al Holbert, a universally respected sporting diplomat who knew the American racing scene like the back of his hand. One former member of the 1980 team was missing when Porsche made its second attempt on the Indy: in 1982 Danny Ongais had suffered severe head injuries in an accident at Indianapolis and was no longer available to drive the new Porsche. Hence the driver question was once more wide open.