Guy Moll

#1

Posted 05 August 2003 - 18:21

Advertisement

#2

Posted 05 August 2003 - 19:34

#3

Posted 06 August 2003 - 00:18

#4

Posted 06 August 2003 - 08:44

I might be wrong but I think Mark Hughes's article in Motorsport August 2003 is flawed. Guy Moll's first race was in the 6 Heures de Tunis in 28/3/1931 where he finished 5th on handicap driving a Lorraine-Dietrich. The race was won by Luigi Castelbarco and Rene Dreyfus with a quasi-sports Maserati 26M, hardly a "small-time" amateur event! Yes, as Hughes states Lehoux was there for the Grand Prix the following day but it was a year later when Lehoux agreed to take Moll under his wing and lent him a car for the race at Oran 24/4/1932.

I cannot be bothered to write to Motorsport. Can anybody confirm my assertion? Marcor?

From his debut to his fatal crash at Pescara 15/8/1934 Guy Moll competed in just 27 races. He retired in 9 and was unluckily disqualified in another. Of the 17 races he finished he was "on the podium" 14 times! His two victories were at Monaco and the AVUS; two very different circuits.

He was talented and brave to the point of recklessnesss, like Nuvolari. He could have been one of the all-time great drivers had not Fate decreed otherwise.

John

#5

Posted 06 August 2003 - 17:40

Jody Scheckter?

Wrong!

See Classic Car Africa

July 1998

Vol 3 No 4

"Guy Moll - the Commendatore's pet"

#6

Posted 06 August 2003 - 18:28

Originally posted by humphries

Lemans

I might be wrong but I think Mark Hughes's article in Motorsport August 2003 is flawed.

John

Perhaps Mark Hughes used this for at least some of his research:

http://8w.forix.com/moll.html

#7

Posted 07 August 2003 - 22:33

One year later, he finished 5th - as you said - in the 6 Heures de Tunis. Some days after (on April 15), he started his 1 year long military service. So, in April 1932, he was ready to compete again at Arcole where he met Marcel Lehoux.

#8

Posted 07 August 2003 - 23:55

You are dead right. Moll's debut appears to be 1930. So Hughes was two years adrift.

Moll was in the first three 14 times out of 18 finishes; still impressive.

As a matter of interest was the Veyron who finished 7th, I think, in this 1930 Oran sports car race driving a EHP, the same famous Pierre Veyron of later seasons?

John

#9

Posted 17 August 2003 - 10:09

Guy Moll’s Last Race

Guy Moll was a rising star in 1934. That season, Chiron and Moll were the leading drivers in grand prix racing. Chiron was already a proven champion, but how was it that a 24-year old newcomer could share the limelight with Chiron? Guyllaume Moll, the son of a Spanish mother and French father, was born in 1910 in Algeria, which was still a North African French colony in 1934. Moll, who looked somewhat older than his actual age, came from a well to do Jewish business family in Algiers, so he could afford to purchase good racing cars and to maintain them properly. The ambitious Moll possessed the ability to drive at the highest level, higher than most other drivers and including some with significantly more racing experience. He finished in more races than many drivers who had longer careers; and when he finished a race, he was amongst the leaders.

Guy Moll's first race was in 1930, when he was only 20. It was the 168 miles Oran sports car race on the Arcole circuit, where he came fourth with an older Lorraine-Dietrich behind the Bugattis of Czaykowski, Vincenti and Molar. Moll drove in several North-African events and, as pupil of his38 year old countryman Marcel Lehoux, he raced Lehoux's T35C Bugatti in some events. In April 1932, he retired from the Oran GP in Algeria early on due to mechanical problems with the Bugatti T35C. The following month, at the Casablanca GP in Morocco, he again retired the Bugatti. In September that year, he came to Europe to purchase a Bugatti T51 from Ernst Friderich, the Bugatti dealer in Nice. Moll entered his new car in the Marseille GP where he came third behind Sommer and Nuvolari, both in Alfa Romeos. This was an extraordinary achievement in his first truly international race, for he finished ahead of Chiron, Dreyfus, Fagioli and Varzi.

With the Bugatti T51, he finished second in February of 1933 at the Pau GP behind his countryman Lehoux, after having led the early stages through a snowstorm. It had become obvious that Moll was not only a fast driver but he also drove intelligently. At the Tunis GP the following month, he came home ninth. Then, in June, he bought himself a 2.3-liter Alfa Romeo Monza and with it, he came third in the Nimes GP behind Nuvolari and Etancelin. The following week, Moll was fifth from 19 drivers in the all-important French Grand Prix. However, three weeks later at the Marne GP, he was disqualified for receiving outside help and, at the Belgian Grand Prix in July, he suffered further frustration when he retired with a gearbox problem. The following month at the Nice GP, he came third with his Monza behind Nuvolari and Dreyfus, both of whom drove cars that were more powerful. Two weeks later at the Comminges GP, he was third behind Fagioli and Wimille and a week later he was again third at the Marseille GP behind Chiron and Fagioli with stronger machinery. In September , Moll came eighth in the Italian GP and later in the day, during the tragic Monza GP, he made the fastest time of the day on the banked high-speed track. He came second behind Czaikowski in Heat 1 and, in the Final, he again came second, this time behind Lehoux.

Guy Moll’s outstanding talent was instantly realized by Enzo Ferrari who asked the 23 years old Algerian to join the Scuderia Ferrari, Alfa Romeo's official racing team, in 1934. Almost immediately, he won his first race, the Monaco Grand Prix, in a 2.9-liter Type B Alfa Romeo P3. He was a trifle lucky, as his teammate, Chiron, made a mistake on lap 98 of 100 when he was leading Moll by 90 seconds. Chiron ran his car into the sandbags at the Station Hairpin and, while he hastily heaved his car out of the sandbags and restarted it, Moll went past him, maintaining his steady, fast pace, to win by over one minute.

At the beginning of May at the Tripoli GP, Moll gave a demonstration of his indomitable determination to win. Throughout the race, he was always in the leading group behind Taruffi, Chiron and Varzi. Having looked after his engine and taken it easy in the early part of the race, towards the end Moll closed the gap to the battling leaders, Varzi and Chiron. All three were driving for the Scuderia Ferrari in the same Type B Alfa Romeos. So, Moll did not have a faster car; instead, he drove the fast corners of Tripolis with greater precision and more courage than his teammates. Five laps from the end he had caught Chiron, whom he then passed. He then set out after Varzi. As they went into the last lap, Moll was just a few yards behind Varzi with Chiron five seconds behind. Moll tried to pass on the inside of the last wide turn leading into the finishing straight but Varzi closed the door on him and Moll had to move on to the sandy strip on the inside edge of the track next to Varzi. The spectacular, flat out chase down the final stretch to the finish line ended in a photo finish with Moll one car length or 2/10 of a second behind Varzi. This was the closest finish ever seen. After the race, Moll accused Varzi that he had tried to push him off the road. Enzo Ferrari did not get involved but responded by letting the Algerian test a specially bodied Alfa P3 for the upcoming Avusrennen on the Milan-Laghi Autostrada.

The Avusrennen came at the end of May, and Enzo Ferrari, who rated Moll very highly, decided that the Algerian was to lead the attack against the Auto Unions. He was given the Scuderia’s fastest car, a special 3.2-liter streamlined Type B Alfa Romeo and won the race, beating Varzi by 1½ minutes. Moll received a stormy reception from the crowd; for being a Jewish driver, it was not a popular victory with the Nazi big shots watching from the grandstand. The following weekend at the Montreux GP, Moll retired early on, but in July at the French Grand Prix, he came third, sharing Trossi's car. Then, one week later at the Marne GP, Moll came second behind his teammate Chiron. At the German Grand Prix, he retired with gearbox problems and, still in July at the Coppa Ciano he came second behind his teammate Varzi, beating Nuvolari's Maserati in third place.

Wednesday, 15 August, came the tenth running of the Coppa Acerbo at the Pescara circuit on the Adriatic Sea. It was to be Guy Moll’s last race. Minister Giacomo Acerbo had named the race in honor of his brother Capitano Tito Acerbo, a decorated war hero, who was killed during the last year of WW I. The first race was held in 1924 when Campari burst a tire on his Alfa P2 and had to retire as he carried no spare. Enzo Ferrari in an Alfa RL then won the race from Bonmartini's Mercedes. In 1934, the same road circuit was in use. It was triangular in shape like Reims, consisting of regular roads with all the normal road hazards. The Start Finish line was outside the seaside resort of Pescara, where the road went straight for about ¾ mile along the shore. At the following right turn, the circuit headed inland for about seven miles along a winding road up into the Abruzzi Mountains, through forests and the hill villages of Villa Raspa, Montani, Spoltore, Pornace and Villa S. Maria, rising to 623 feet above sea level. Then began the descent to Capelle sul Tavo where there was a slow right hairpin exiting under a bridge. From here, the road led into the about seven miles long Monte Silvano downhill straight to the coast at blistering speed. This was the fastest stretch of the circuit and included a one kilometer timed section, which was on a slightly downhill incline. The Monte Silvano straight was followed by a fast right turn at Monte Silvano railroad station, which led into the Lungo Mare straight along the coast back to the start. To slow the cars on that sea-level straight, a large artificial chicane was introduced for 1934 just before the Start-Finish area, to reduce the speed as cars passed the pits. This change resulted in a marginally increased circuit length from 15.906 miles to 16.032 miles. (In 1935 two more chicanes were to be installed in the middle of each straight to give the Italian cars a better chance.) The Coppa Acerbo was Italy's second most important Grand Prix Race and consisted of 20 laps, making a total of 320.640 miles.

All major teams and drivers were present. Auto Union had two cars for Hans Stuck and reserve driver-mechanic Wilhelm Sebastian. Leiningen had already fallen sick before the German GP and Momberger, the third driver, had hit his head on the headrest when he went over a dip in the road during the race itself. He had to be relieved by Burggaller because of a bleeding head wound. Team Manager Willi Walb decided the following week that Wilhelm Sebastian was to take Momberger's place in Pescara, driving the latter's car used at the German GP. Stuck's car was also the same as raced at the German GP, but both cars received the high axle ratio used at the Avus, plus improved brakes and better venting. Daimler-Benz had three W25 cars for Caracciola, Fagioli and Henne in place of von Brauchitsch, who had broken his arm a month previously when he crashed during practice for the German GP. Hanns Geier, one of the two reserve drivers, had driven at the Nürburgring, but at Pescara it was Ernst Henne's turn. This was to be his first Grand Prix start, nevertheless, during practice, he set the fastest speed through the timed kilometer at 300 km/h or 186 mph. As usual, Alfa Romeo had the Vittorio Jano designed P3 cars entered by Scuderia Ferrari with Louis Chiron, Achille Varzi, Guy Moll and Pietro Ghersi at their disposal. Bugatti entered a lone T59 for Antonio Brivio. Secondo Corsi in the 16-cylinder V5 and Goffredo Zehender in an 8CM represented the Maserati factory. Tazio Nuvolari, Whitney Straight, Earl Howe, Felice Bonetto and Hugh Hamilton also drove 8CM Maserati's but they were privately entered. Penn-Hughes with a 2.3-liter Alfa Romeo Monza was the last of the privateers.

A voiturette race had preceded the main event and with the Scirocco wind blowing, it had rained during the half hour interval to the start of the Grand Prix. The drivers prepared for a wet race. Caracciola's familiar white overalls were covered with waterproof clothing. Cockpits of the cars on the grid were covered up and tires were changed from smooth type to ones with road-racing threads, better suited for a wet circuit. Although it had stopped raining at the time of the start, the track was still wet and slippery. Bonetto’s Maserati did not show up and 17 cars stood ready on the starting grid, with three different makes placed on the front row.

28 54 44

Caracciola Varzi Stuck

Mercedes-Benz Alfa Romeo Auto Union

30 50

Nuvolari Fagioli

Maserati Mercedes-Benz

48 58 40

Penn-Hughes Corsi Straight

Alfa Romeo Maserati Maserati

56 60

Howe Zehender

Maserati Maserati

34 46 36

Henne Moll Chiron

Mercedes-Benz Alfa Romeo Alfa Romeo

52 32

Brivio Sebastian

Bugatti Auto Union

62 64

Ghersi Hamilton

Alfa Romeo Maserati

There was great excitement as they roared and screamed away, leaving a cloud of sweet scented haze. The Auto Union of Hans Stuck shot into the lead, followed by Varzi's red Alfa Romeo and Caracciola's #28 Mercedes-Benz. During the first minutes, Stuck, Varzi and Caracciola swapped places on the winding run through the hills. Then 'Rainmaster' Rudi passed Varzi for the last time at the beginning of the long run down to Monte Silvano and overtook Stuck at the end of the straight just before they reached the fast right turn at the sea. At the end of the first lap, Caracciola led Stuck and Varzi by two seconds, with the Italian attempting to pass Stuck. There was a 22 seconds gap to Fagioli in fourth, followed by Moll, 200 yards behind. Next came Hamilton, Henne, Chiron and Zehender.

On the next lap, Stuck and Varzi lost time as a result of their battle for second place. Caracciola in contrast, drove flat out and on the Monte Silvano straight was timed at 181.4 mph. When he passed the pits, his advantage to Stuck and Varzi had increased to 500 meters, followed by Fagioli further back. Moll pulled into his pits to have a spark plug changed and lost one minute. During that time, Hamilton went by, ahead of Chiron and Nuvolari.

On lap three, the fight for second place intensified as Varzi made several serious but unsuccessful attempts to pass Stuck in the winding section, and remained glued to the Auto Union's tail. On the long straight down to Monte Silvano, Varzi drew level at top speed, racing wheel to wheel up to the fast right turn leading into the coastal straight and took second place. Caracciola's third lap speed averaged 82.802 mph but Stuck, still in third place, had already fallen back, and was signaling to the pits. He was now closely followed by Fagioli. Further back was the battling trio of Hamilton, Nuvolari and Chiron in that order. Moll pitted for the second time for yet more spark plugs, which dropped him even further back.

At the end of the fourth lap, Caracciola had increased his advantage. Stuck now found himself in second place again after Varzi had stopped at his pit to change front wheels, as the right front tire had stripped its thread. Simultaneously, he topped up with fuel and the stop cost Varzi 85 seconds. Meanwhile Moll was driving in very determined fashion to make up lost time.

On lap five, Caracciola continued to pull away, further increasing his advantage. Stuck in second place slowed his pace and was passed by Fagioli. Then came the motivated Nuvolari who had worked himself up to fourth, followed by Hamilton, Chiron, Henne and Moll. After the completion of five laps, Stuck pulled his Auto Union into the pits, retiring with a blown piston. Varzi stopped at the pits again, but this time his Alfa was retired with gearbox failure.

By lap six, Caracciola had build up a massive advantage, with Fagioli second, Nuvolari third and Chiron fourth, now 3m48s behind the leader. Moll received signs from his pits to drive faster and Scuderia Ferrari stopped Ghersi's car, to let Varzi take over. At the end of lap six, Caracciola led Fagioli by 1m46s and Chiron by 3m58s, followed closely by Henne in fourth place. Nuvolari had to stop at his pit with a misfiring engine and it took four minutes until an obstruction in the fuel lines was found. Moll, after having cured his misfiring engine, was now driving very rapidly. Further back came Varzi in Ghersi's car, making up lost ground. Hamilton slowed down as he encountered problems and at the same time, Whitney Straight's race ended due to mechanical problems.

At the end of lap seven, Caracciola's advantage had grown to five minutes. Fagioli was still second, possibly having lost time with an off-road excursion and Henne, in third place, made it a Mercedes one - two - three. Chiron pulled slowly into his pits with a misfiring engine, changing plugs and taking fresh fuel, all of which took 2m30s. During Chiron's delay, Moll sped past the grandstand, then Varzi with a lap at 141 km/h.

On lap eight, Moll caught up with Henne and passed him for third place after Monte Silvano Station on the Lungo Mare straight. At the end of lap eight, the order was Caracciola, Fagioli, Moll, Henne, Varzi in Ghersi's car and Chiron, now in sixth place. Hamilton, in the 8CM Maserati retired with a broken piston.

The ninth lap brought major changes, which entirely altered the complexion of the race. Caracciola, who had led for eight laps, made one of his rare mistakes and spun off the track. In Molter's book 'RUDOLF CARACCIOLA', Rudi said that the road was slick as glass as he went down a straight at 200 km/h. As he approached the following curve, he very delicately felt the brakes but he had the same feeling as in Monte Carlo (1933). Did the wheel lock up? The next moment, the car spun around and flew diagonally backwards up an embankment. On top, the tail of his car grazed a fence very slightly, but enough to spin it around again, landing on the road facing in the right direction. This incident was obviously just a warning because shortly afterwards, at a place where Fagioli had already left the track, his car did half a roll to the left and disappeared with a loud crash into a four meter deep ditch. He was lucky to escape without injury but the car was badly damaged.

At the end of lap nine, Fagioli, now in first place, stopped for fuel, changed wheels and had new spark plugs fitted. During his lengthy pit stop, Guy Moll screamed past the grandstands into the lead and the crowd roared with excitement. With the mechanics still working on Fagioli's car, Henne passed the grandstand 20 seconds ahead of Varzi in Ghersi's car. However, the latter stopped at the pits for 70 seconds and got away after Fagioli had left. Brivio's Bugatti lay fifth, followed by Nuvolari.

Chiron arrived next and stopped at his pits with a badly misfiring engine. Not sure whether the problem was due to spark plugs or fuel feed, the engine was left running. While one mechanic tested spark plugs and the other checked fuel lines, Chiron remained in the car operating the accelerator. Gasoline squirted from a loosened fuel pipe and was ignited by an electric spark caused by the other mechanic testing the plugs. Instantaneously the car burst into flames, the fire spreading from the engine to the tank, fed by the fuel squirting from the pipe. The spectators watched in horror as Chiron’s overalls caught fire, mechanics helped the flaming driver from the cockpit, while he covered both eyes with his hands and staggered away from the burning car. Chiron received only slight burns to face and neck, because an official immediately beat out the flames. The blazing Alfa Romeo stood dangerously close to the pits where drums of gasoline were stored while the car kept burning fiercely. People around started fleeing the volatile scene fearing the worst. Eventually, with the help of extinguishers and sand, the fire was put out after ten minutes, but the car was totally burned out and parts of the pits were also destroyed. All this excitement almost obscured the fact that Corsi, in the 16-cylinder Maserati, had seriously crashed his powerful car when he veered off the road breaking some ribs.

At half distance, after ten laps, Moll had averaged 126 km/h, leading Henne by 32s, Varzi in Ghersi's car by 1m1s and Fagioli, who was one second behind him in fourth place. Nuvolari was fifth, followed by Sebastian's Auto Union, Brivio's Bugatti and Penn-Hughes' Maserati. Zehender, Howe and Hamilton had all retired by this time, which made Nuvolari the only surviving Maserati driver out of six at the beginning of the race.

During lap 11, Moll maintained the lead and Varzi, who was now driving very rapidly, passed Henne into second place. At the end of the lap, the two red cars were in front with the two Mercedes third and fourth. At the completion of the twelfth lap, Moll made a refueling stop, which promoted Varzi to first and Fagioli to second place.

Lap 13 saw Varzi in the lead, Fagioli second, followed by Moll, one minute behind when he roared away from his fuel stop. The Mercedes pit had signaled their drivers to speed up. Moll’s Alfa was now ready for the final battle and the Algerian tried to make up the time lost during his pit stop. Meanwhile, Henne skidded dangerously at the artificial curve before the pits, which lost him so much time that the hard charging Nuvolari overtook him.

At the end of lap 14, Varzi pulled into the pits to replace his fast wearing rear tires and fill the car with fuel. His stop of 1m55s enabled Fagioli to take the lead and Moll moved into second place. Varzi was now third and Nuvolari a distant fourth. At the end of the next lap, Fagioli led Moll by 37 seconds, Varzi by 1m41s and Nuvolari by 5m24s. Then followed Brivio's Bugatti, Sebastian's Auto Union and Henne's Mercedes-Benz, who had fallen to last place.

Guy Moll was undaunted and was now the only one able to race on level terms with Fagioli’s more powerful Mercedes. The dramatic race had developed into an electrifying hard-fought battle. The Algerian was driving faster than ever, knowing that the hopes of Italy rested on his shoulders. His motivated drive resulted in a new record lap of 10m51.0s at 101.398 mph on lap 16. Fagioli's lap time was 10m59s, which reduced his advantage to only 29 seconds. The tension was building because the outcome of the race was uncertain. Could Moll win for Italy in the red Alfa Romeo? At the end of lap 17, Moll entered the artificial turn before the pits too fast, ending up in a lurid slide, the Alfa skidded broadside and stalled. The Algerian had to get out and start his car with the crank. Despite all this, his lap time was still 11 minutes flat and he would no doubt have broken his previous lap record, if he had not stalled the car. Varzi came slowly into the pits as the car had lubrication problems and Ghersi took over with instructions to nurse the Alfa to the finish.

The tropical heat turned the cars into real ovens. The weather had been inconsistent all day and the Scirocco, a rather strong wind with sporadic squalls and rain showers, was blowing. This made it even harder to drive the powerful cars at their top speed because they already needed the whole road when driven flat out.. Henne was measured doing 183 mph and Caracciola 182 mph early in the race. But after Henne twice ran into problems and the Scirocco picked up in force, the German slowed down in the second third of the race. On lap 18, Moll went faster through the winding section than he had ever done before. He was closely following Henne through the Capelle hairpin and as they entered the downhill Monte Silvano straight, Moll attempted to overtake the German’s Mercedes, which was now a full lap behind. The German did not expect Moll to pass on this narrow section where he needed almost the full width of the track just to keep the Mercedes on the road. A passing maneuver would be just too dangerous. But instead of waiting for one or two miles until the road widened, the inspired Moll gradually pulled alongside the German. Moll was slightly in front of Henne's Mercedes, when the Alfa Romeo fell back, moved too far to the left, the wheels slid over the road edge and veered into the shallow ditch at the side of the road. For about 50 meters the car remained straight with Moll braking and trying frantically to regain the road. Then one front wheel struck a low stone pillar, which was part of the wall of a small bridge. The impact at over 155 mph caused the car to vault into the air, somersaulting high, flinging out Moll. He was killed instantly. The car kept tearing through telegraph wires, tumbling repeatedly, felling some young trees and crashing down until it came to rest at the side of a house after 300 to 400 yards. The spectators who hastened to the site found Moll's lifeless body on the opposite side of the road against a concrete post.

The exact cause of this crash will probably never be known. Statements from various accounts are contradictory and Moll's death was most likely instantaneous. Did a sudden gust of the Scirocco cause Moll to drift off the road? In Chris Nixon's book, 'Racing The SILVER ARROWS', Ernst Henne said, he could see that Moll wanted to pass him at a stretch were the road was very narrow. As they were doing about 170 mph downhill, Henne could see out of the corner of his eyes as Moll tried to pull alongside him only to fall back, but their cars never touched. There were different versions of what happened and, later on, groundless accusations were made that the cars touched, trying to put the blame of the crash on Henne, whose driving was described as wild and suspect. However, he was an easy target since this was his first grand prix race. Even though he had raced motorcycles for ten years, he was inexperienced driving these fast, poor handling cars. Guy Moll's dreadful crash in essence ended the race, which came to a somber end with the full 20 laps completed. Nobody was left to challenge Fagioli, who after 3h58m56.8s finished the race first, 4m38.2s ahead of Nuvolari’s Maserati, followed by Brivio’s Bugatti, Ghersi’s Maserati, and one lap behind by Sebastian’s Auto Union and Henne’ Mercedes-Benz last. From the 17 cars at the start, only six finished. So ended a meteoric, but tragically short racing career. Guy Moll was put to rest in the Maison-Caree cemetery in Algiers.

#10

Posted 17 August 2003 - 11:26

Marc, do you know something about Cyaikowski's car in this race?Originally posted by Marcor

... Sportscars race included in the Oranie GP meeting (at Arcole), race won by Stanislas Czaikowski. The date: April 27.

And, I have only 13 'podiums' in my list about Moll. Which one is missing?

1932

3. Marseille

1933

2. Pau

3. Nimes

3. Nice

3. Comminges

3. Marseille

2. Monza

1934

1. Monte Carlo

2. Tripoli

1. Avus

3. Monthlery

2. Reims

2. Livorno

And, Hans, thanks for that wonderful story.

#11

Posted 18 August 2003 - 16:11

2)- Veyron. Yes Pierre Veyron.

David Venables, in his book "The Racing Fifteen-Hundreds", wrote that Pierre Veyron, born in Lozere (South of France) in 1903, began his racing career in1930, driving an EHP in the Mont Ventoux hillclimb (August, 24).

In fact, he started racing in early spring of the same year. I have records of him as winner of the Sport 1500 cc class at La Turbie (March, 23) and L'Esterel (March, 29). He then crossed the Mediterranean to take part in the Oran race. In 1930 he also took part in a sprint at La Moyenne Corniche, near Nice (November, 11).

3)- Last podium: not really one but ...

Before Moll was disqualified at Rheims in 1933, he had finished 3rd.

#12

Posted 18 August 2003 - 17:57

#13

Posted 18 August 2003 - 18:43

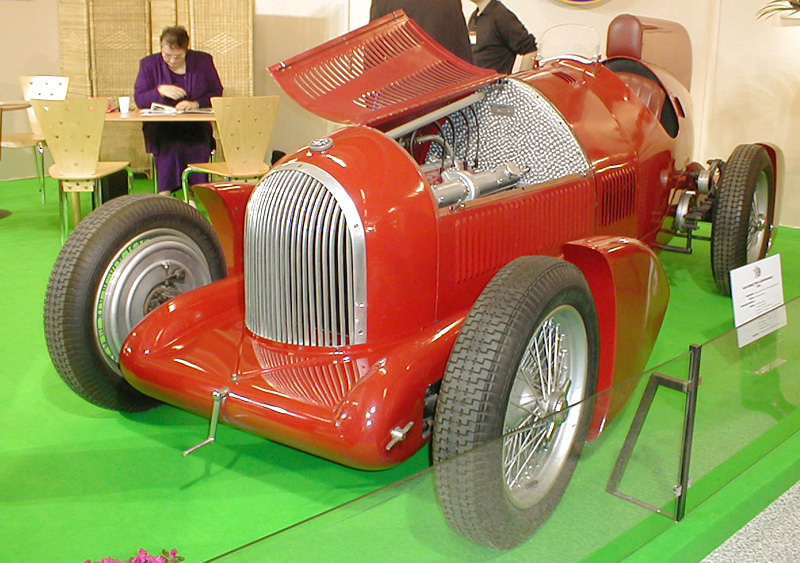

Are there any period pics of that car racing? I only know one testing pic, as shown in Cimarosti.

And also I know only one scale model of that Alfa, a beautiful Metal 43 kit. Is that really the only one?

#14

Posted 19 August 2003 - 13:21

Originally posted by dmj

I heard they say that one picture says more than hundred words...

Are there any period pics of that car racing? I only know one testing pic, as shown in Cimarosti.

And also I know only one scale model of that Alfa, a beautiful Metal 43 kit. Is that really the only one?

There are indeed some pictures of the real car, since this is actually a reconstruction, albeit carried on by the Alfa Romeo museum, under direction of the late Luigi Fusi. It's featured, from the top of my memory from every angle, both before and during the AVUS race, with a #64 race number.

I have made a quick search on the net for one of those period pictures, unfortunately to no avail, but there are more pics of the replica around, including this one:

The models I know of include a quite rare ABC (Carlo Brianza) limited edition, dating back 15-20 years, to be found only on swap meeets at substantial prices, or a very new kit, resin cast, from a french man called Mardon, which I incidentally happened to buy one example a few days ago. To me, it looks like an ABC remould. I haven't kept picture of it, but can provide to anyone the address of the maker/seller if wanted (usual disclaimer...)

#15

Posted 14 March 2007 - 13:34

But I have only 26 races in my list about Guy Moll. Which one the missing?

1930

Oran

1931

Tunis (6 hours)

1932

Oran

Casablanca

Marseille

1933

Pau

Tunis

Nimes

Montlhéry

Le Mans

Reims

Nice

Comminges

Marseille

Monza (Italy GP)

Monza (Monza GP)

Brno

1934

Monaco

Tripoli

Avus

Montreux

Montlhéry

Reims

N'ring

Montenero

Pescara

#16

Posted 14 March 2007 - 21:07

I think we need a thread merge 'here - we've got two Guy Moll threads running in parallel right now...

#17

Posted 14 March 2007 - 21:11