So, here goes: Remember, I haven't done a thing with this corpse since 2001, and its probably a bit rough around the edges. Also, like David I had assembled every picture I could find of the thing, but they are in a different folder - will try to find them as well and edit them in.

Curriculum Vitae - The Story of the Life A detailed history of the worst-ever Grand Prix car August 24, 1990: On one of my very infrequent visits to Formula 1 Grand Prix meetings, I am sitting on a grandstand adjacent to the famous rise between Eau Rouge and Raidillion corners, part of the Belgian Spa-Francorchamps circuit. It's Friday morning, a quarter to nine, and only a small crowd of die-hard fans is present to witness the pre-qualifying session for the Belgian GP. It's not a glamorous job for the drivers, pushing a dog of a Formula 1 car of some impoverished end-of-pit-lane team through its paces merely to gain admission to the main game, a fact only too obviously demonstrated when, during the course of the day, Swiss driver Gregor Foitek, only just a fortnight bereft of his drive in the uncompetitive Monteverdi/Ford (née Onyx/Ford), enters the meanwhile brimming grandstand and sits down just a few of feet from me, acknowledged by exactly no one! The withdrawal of his team has taken the burden to pre-qualify off the once famous Ligier team, and thus diminished interest in this little side-show even further, to the point that only six 'nameless' cars circulate the Ardennes track in the cool of the emerging day. Fastest is Olivier Grouillard in the Osella/Ford, with a time just under 1'58", and to the delight of the home crowd it's Bertrand Gachot's Coloni/Ford in second, while the two AGS/Fords of Yannick Dalmas and Gabriele Tarquini struggle so far to keep the EuroBrun/Fords of the mercurial Roberto Moreno and Claudio Langes at bay, the four of them lapping just outside the two-minute mark.

Then, apparently out of the blue, a red car leaves the pit lane, accompanied by a huge cheer from the spectators. A Ferrari in pre-qualifying? As the car pulls up the small hill, emitting horrendous sounds and barely making the top, it soon becomes apparent that the cheers and the smiles on the faces of the onlookers are signs of amusement, rather than enthusiasm. Even today, I still wonder how many of them were actually aware of the fact that they now belonged to the very chosen few who had witnessed the worst Grand Prix car of all time in action! A sight indeed to behold... Gary Brabham was arguably the least talented of the three sons of Australia's three-times World Champion Jack Brabham, but he was far from being a slouch at the wheel of a racing car. Between 1986 and 1988, he had won six British Formula 3 Championship rounds with a Ralt/Volkswagen, finished second also six times and once third, which ultimately resulted in the runner-up spot in the 1988 championship, behind J. J. Lehto and ahead of Damon Hill, Martin Donnelly and Eddie Irvine, no less! The following year, he graduated to Formula 3000, and though he managed only one points finish in the International Championship (5th at Brands Hatch), it was one of only two for the Leyton House-March chassis all year. Better still, he also drove a Reynard/Cosworth in the British Formula 3000 Championship, winning four out of nine races, finishing second twice and once third, in the process of beating Andrew Gilbert-Scott and Roland Ratzenberger to the title to complete a memorable year for the Brabhams, thirty years after the first World Championship for Sir Jack: His older brother Geoff successfully defended his IMSA Sports Car Championship with a Nissan, while younger brother David won the British Formula 3 Championship in a Ralt/Volkswagen - Amazing!

Due to his latest success, Gary was granted a super-licence to compete in Formula 1, and thus he signed a two-year contract with Life Racing Engines in January 1990. Whether he knew more about this new Formula One team than the outside world is quite debatable, and so the future looked as bright to the 28 years old and, from now on, Italian-domiciled Australian as it could have. After all, Ernesto Vita's team from Formigine near Modena was all set to enter Grand Prix Racing with a revolutionary new engine, christened the Life F35, and designed by former Ferrari employee Franco Rocchi: a W12, uniting the advantages of short overall length of a V8 engine with those of superior rpm of a 12-cylinder unit. It had three banks of four cylinders each, arranged in the shape of an arrow and angled at 60°, with a bore of 81 mm and a stroke of 56.5 mm, giving 3,493.7 cc. Its maximum rpm were given as 12,500 and the compression ratio as 13:1, with a total weight of 154 kg. Fuel injection and ignition by TDD were to be used, and spark plugs by Champion. Another reminder of the fame of nearby Ferrari was the Italian oil company Agip, who were to supply and sponsor the team.

Having a shiny new engine was one thing, but the days of buying a proprietary chassis from an acknowledged specialists were over since the days of the infamous Concorde Agreement in 1981, and thus not a viable option for the fledgling team. Over in France, Guy Negré and his MGN company had much the same problems and tried to attract the AGS team to run their similar W12 unit, but to no avail. In Italy, apart from Ferrari, there were quite a number of teams trying to gain a foothold in F1, but neither Osella, BMS Italia, Minardi, EuroBrun or Coloni were willing to gamble on the unproven engine, relying instead on the time-honoured Ford Cosworth or, in the case of the latter, an alliance with a big manufacturer like Subaru. Besides, there was always the hope to acquire customer engines by Lamborghini or Ferrari, so why bother with Life?

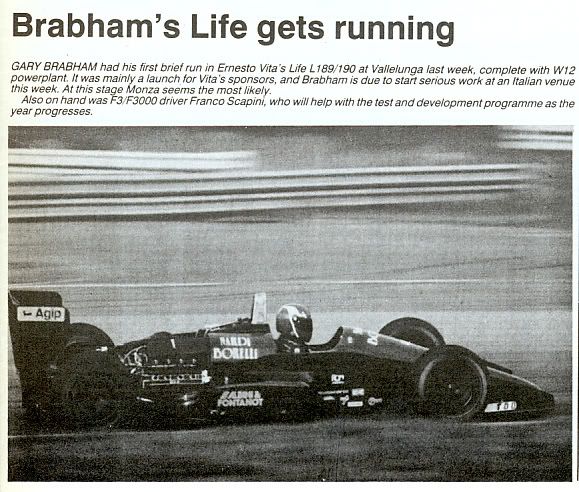

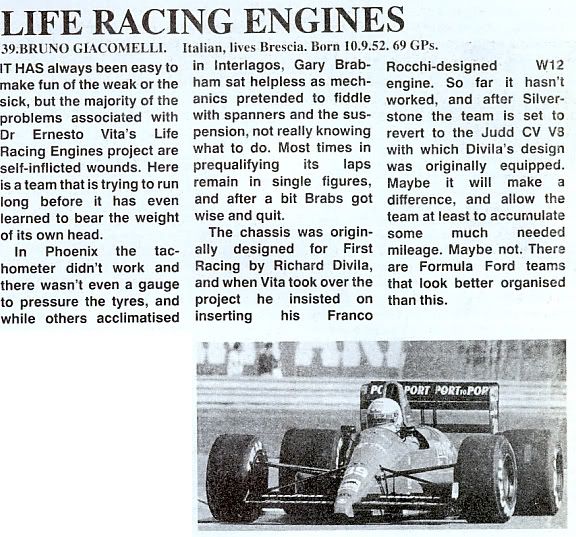

Luckily for Vita, there were almost as many F3000 teams in Italy willing to take the plunge into F1, and one of them, Lamberto Leoni's FIRST Racing team, had actually built a car in 1988, to be powered by a Judd CV engine. When the financial background did not materialise, Leoni was only too happy to sell the one-off chassis to Vita, who began track testing his Life F35 engine in this car, now dubbed Life F190, in 1989. Initial design studies for the FIRST had been by Ricardo Divila (of Copersucar/Fittipaldi-"fame" and by now working for the Brabham team), but the final execution had been in the hands of one Gianni Marelli, resulting in a totally conventional car with double-wishbone suspension all around, and pushrods activating the Koni dampers. At 2.78 m it had the shortest wheelbase of all in the 1990 season, making full use of the engine layout. Front (1.81 m) and rear track (1.657 m) were also of conventional dimensions, and the power of the W12 engine was transmitted via a home-built 6-speed gearbox, with Hewland internals, and an AP clutch. Tyres were supplied by Goodyear, and brake pads for the Brembo brakes by Carbone Industries. The 200-litre fuel tank was provided by Pirelli, the radiators by Secan, instruments by Stack, batteries by Fiamm and the steering by Pignone e Cremagliera. In all, the car was said to weigh in at 530 kg, making it rather a heavyweight compared to its rivals which usually weighed no more than the compulsory minimum of 500 kg.

The late withdrawal of the two German F1 teams, Rial and Zakspeed, left an entry of just 35 cars for the 1990 FIA Formula One World Championship, compared to the record 39 of the year before. Still, with a maximum number of 30 cars allowed for the main practice sessions under the Concorde Agreement, the continuation of the pre-qualifying procedure was necessary. The rules stipulated that, apart from 26 seeded cars (determined by the success of their entrants in the two previous half seasons of the World Championship), every car had to take part in a special practice session on the first day of a Grand Prix meeting, with only the four fastest in that session allowed to take part in the remainder of the meeting. As a new team, Brabham and the Life were thus one of nine competitors who were obliged to slug it out between 8.00 am and 9.00 am on Friday mornings, meaning that track time was a prerequisite if they wanted to stay a chance to survive this early sieving.

First tests were envisaged for late January, at the Misano Santamonica track, but did not happen before February 8/9 at Vallelunga, where Brabham managed no more than a few laps. Later that month at Monza, electrical problems stopped the team after only 20 more laps. Italian F3000 makeweight Franco Scapini was recruited as the new test driver for the team, but time was pressing and the car was shipped to Phoenix for the United States Grand Prix with barely 100 miles on the clock. As it was, not much was added to that figure in the Arizona desert city, when after a first flying lap in 2'07.147" Brabham went back into the pits to report a misfire, whereupon all the plugs were changed in approximately 10 minutes. Gary went out once more, did a 2'24.966" warm-up lap and then stopped out on the circuit with an ignition box failure, just 22 minutes into the one-hour session. It did not matter that the car was not retrievable in time, since the team had no spare box available anyhow, and that was that.

Fastest in this session had been Roberto Moreno in his EuroBrun/Ford, with a time of 1'32.292". He had also recorded the fastest speeds at the two "speed traps", 266.16 kph at the end of the back-straight and 241.31 kph at the start/finish-line. For the remainder of this article, I will always use the best performances of any given session as the basis (

100) of an index to show the relative performance of the Life and, for evaluating purposes, other competitors. At Phoenix, Aguri Suzuki in a Larrousse/Lamborghini captured the last spot qualifying for promotion into the real thing, at an index value of

98.887. Gary Brabham and the Life managed only

72.587, and a top speed of 185.57 kph (

69.721) on the back-straight and 178.28 kph (

73.880) at the start of their flying lap. Amazingly, with this sort of performance they still ranked only second to last, since Bertrand Gachot's new and untested Coloni/Subaru (well, actually a year-old chassis with an old-fashioned Motori Moderni engine) managed only one very slow lap when the gear linkage broke as soon as it left the pits!

Things couldn't possibly get worse, could they? Two weeks later, the Brazilian Grand Prix was to be staged at a refurbished Interlagos track on the outskirts of São Paulo, and two unofficial practice session were scheduled for the Thursday to give the teams a chance to acclimatise to the new circuit layout. A rare opportunity to test for the Life team but, sadly, the day was thoroughly rained off. Come Friday morning, and at least the rain had stopped, though the track was still damp in parts. Along with his eight fellow sufferers, Brabham set off, carefully, to feel his way around the wet patches, equipped with Goodyear wets. At the speed trap at the end of the straight before the Subida do Lago and the twisty infield section, he clocked 151.33 kph (

55.309), and never got back to the pit straight again, a con-rod having broken, and after about a minute of running and not much more than a mile covered, the team was ready to pack up. Gosh!

Much later, Brabham recalled: "When I first visited Life the ingredients were there for a super little team, but by the first race it was pretty obvious that they weren't going to be mixed properly. Half of them were now missing. Eventually, the situation became ridiculous." It transpired that the engine, during its first two outings, had never topped 11,000 rpm. The team was so badly organised, it did not even have a tyre pressure gauge at their disposal, and had to borrow one from the rival EuroBrun team! They had also tried to trick Brabham into believing that a new car would be ready in time for the next race at Imola, and when the Australian called the bluff, he wasted no time in bailing out. His reputation was saved when he found a berth in the Middlebridge F3000 team (subbing for his F1-bound brother David), and drove their Lola/Cosworth to a couple of third place finishes in the International Championship, at Monza and Enna-Pergusa. Though he was consistently out-qualified by his team mate all year, he managed to beat him in the championship, finishing two positions ahead in 11th. The name of the team mate? Damon Hill, future World Champion...

Now Life had to scrounge around for a replacement, and already in Brazil, Bernd Schneider was contacted, but the former Zakspeed driver declined the offer. How many others received invitations is open to speculation, but probably anyone with a remote chance for a super-licence got a call. While every other team made more or less use of two weeks of testing at Imola, Life was on the brink of liquidation. Scapini was never going to get a super-licence, and everyone else just wasn't interested. There was not even the money to go testing at a circuit less than 50 miles from the team's base, and to top the squad's misery, designer Gianni Marelli opted to quit his post! What next?

Enter Bruno Giacomelli, 37-year old Italian GP veteran. Runaway European Formula 2 Champion in 1978, with eight wins out of 12 races (March/BMW). All-time record holder of pole positions (11) in F2 championship rounds, and second only to Jochen Rindt (12) in all-time wins (11). Alfa Romeo factory driver in Formula One 1979-82, one pole position (USA 1980), one second place (Australia 1980) and one third (Caesar's Palace 1981). 13 races in CART 1984/5, one 5th (Meadowlands 1985) and two 6ths (Mid-Ohio and Laguna Seca 1985) for Patrick Racing (March/Cosworth). Seriously injured in an Interserie sports car practice crash at Zeltweg in October 1986 (Lancia). Returned the following year to continue in sports car (Porsche) and touring car (Maserati) racing, recently test driver for Alfa Romeo CART and Leyton House-March F1 teams. So what on earth did he expect of Ernesto Vita's team? A lifeline, perhaps...

When the usual crop of underdogs assembled at Imola on Friday morning, Giacomelli and the Life were given an unexpected fillip by the absence/withdrawal of one of the successful qualifiers in Brazil: Yannick Dalmas had injured his left wrist in an accident during testing, and since he had also written off the first chassis of the new AGS/Ford JH25 and the replacement wasn't quite ready, he considered it pointless to make an appearance and withdrew. His sceptisism was confounded when his team mate, Gabriele Tarquini, stopped with fuel pressure trouble just after leaving the pits, and so the field was down to seven before the session had properly begun! Bruno took it easy on his first run in the precious Life, reaching 104.44 kph (

35.104) on the straight before Tosa and then 75.01 kph (

30.341) on acceleration at the start/finish-line, when all the coolant was dropped onto the track, a drive belt for the water- and oil-pump having broken. It was 8:08 am, and later on Bruno admitted to never even having engaged fourth gear during that lap...

The razzmatazz of Monte Carlo! There's no place in the world were a Formula One team would want more to shine than the little principality of Monaco at the Cote d'Azur. It's a window of opportunity, where hundreds of big-buck celebs watch the glamour of Grand Prix racing and risk infection with the bug. Impress here, and chances are you impress someone with the means to make waves. Fail to deliver, and you might as well write the year off! For all it was worth, the little outfit made a superhuman effort: After a cautious warm-up lap, Giacomelli felt his way around the daunting circuit and returned a 2'08.851", then 1'56.963", 1'49.672" and 1'46.149"! Incredibly, the Life continued to circulate and Bruno got down to 1'44.157", 1'42.230" and finally 1'41.187" before peeling off into the pitlane! Quite a show! Almost dazed by the sudden bout of reliability, the mechanics fitted qualifiers and with 20 minutes to go, "Jack O'Malley" set off once more, doing a 1'47.501" and, familiarly, stopping at the harbour front/swimming pool with a broken engine.

So how did he compare? Well, his best lap garnered an index value of

86.112, his top speed before the harbour chicane (213.32 kph)

81.466 and his speed on the start/finish-straight (190.69 kph)

80.446, which seems to suggest that Bruno was at least trying in the corners! Still, he remained at the bottom of the timekeeper's list even though the almost as dreadful Coloni/Subaru of Gachot lost all its oil on its third flying lap already and several other runners hit terminal trouble during the session. What's more, he would even have failed to make the grid as far back as 1974, even allowing for an optimistic 10 seconds adjustment to his lap time due to the two circuit modifications in 1976 and 1986! And, whisper it quietly, all but three of the 35 Formula 3 hot-shoes, trying to qualify for the Monaco F3 race 24 hours later, lapped faster than the Life, with Alessandro Zanardi (Dallara/Alfa Romeo) taking pole position at 1'37.007" (

89.822)...

That's it, as far as I got. I had a few things more

in petto, like the fact that the highest ever recorded speed of the Life was a speed I had already experienced personally on a German Autobahn, at the wheel of a road-going 854 Volvo sedan (!), and actually driven a like car over the same piece of tarmac (Kemmel straight at Spa) faster than the Life...